“My dear friend, I keep your brother’s sad letters like they are relics. I say sad because he always sent me such sentimental letters that sometimes, when I read them, I burst out in tears. I tried to cheer him up, but he was such a sensitive soul that nothing could comfort him.” Letter from Nieves, a friend, to America after she learned of his death.

Galo was the oldest of 11 children, born to a Cuban mother and a Spanish father, in northern Spain, less than a year after their wedding. Back then, male children were always preferred to girls, especially by fathers. Was my grandfather one of those fathers? Even if he wasn’t, I am sure he was thrilled to have a son to pass along his skills to. Working with wood is a long tradition in this family. And back then, passing those skills to a daughter was simply not an option. I still remember hanging out with my father, in his workshop, when I was only 4 or 5, climbing on top of his bench, pestering him to teach me how to do the things he did, how to build furniture, and being told that those were not things a girl could do. When my father finally lost his patience, my mother would take me away so she could teach me more “girl-appropriate” stuff, like cooking and cleaning.

I know very little about Galo’s life before the Spanish Civil War started. Until very recently, all I had was one photograph, a name, and knowing that he had “died” during the war. Now, we know much more. We know that he was working at an electricity generating plant and apparently, he was quite knowledgeable of electricity, and all the mechanical aspects of the plant’s operations. The plant was either owned or operated by one of his uncles and from the letters he left behind, we know that he was living with that uncle when he was working at the plant. I am guessing that once he was old enough, he might have been hired at the plant, and apprenticed there as things typically worked back then when people learned a trade.

But at some point, Galo joined the Republican military. We don’t know if he was already doing compulsory military service when the war broke out or he joined once it did. Whatever the case, he found himself a soldier, fighting to defeat the man who would later become one of the most repressive dictators of the 20th century.

It wasn’t until right before the pandemic that I found out that Galo was taken prisoner by Franco’s troops early during the war, in September of 1937, just a month before Franco captured Asturias and two before his parents were sentenced to death by one of Franco’s military tribunals. His oldest sister Cristina was also sentenced to 15 years in one of Franco’s prisons, her life spared only because she was only 17 when she committed the alleged “military rebellion” crimes she was charged with. Of course, neither his parents nor sister were militants in this war, but that didn’t seem to matter to any of the military officials handpicked to pass judgements on their activities before the war even started.

And it wasn’t until a few months ago that I got to see the letters he wrote to his sister America, his brother Chichi and a couple others, after he became a POW. One of my cousins in Spain found a stash of documents from the civil war that belonged to my aunt America, sometime in the 1990s. He made copies for my parents, but it wasn’t until my mother passed away that I got to see those documents. It was while looking over the scans of the documents that I noticed the signature line in one of Galo’s letters. He would always include the place where he was at when he wrote each letter.

And that letter said he was then at the Hospital Militar de Guernica (Guernica Military Hospital). That caught my attention. I immediately started searching the internet for any information having to do with that hospital. Twenty minutes later, I stumbled upon a website that listed 269 Republican POWs that had died at that hospital. I frantically started scrolling through the pages, and there it was, almost at the very end of that list, on the next to last page, number 242 on that list of 269 men who came from all parts of Spain to die.

The simple line of data told me that Galo died on April 12, 1940, of tuberculosis, at this Military Hospital in Guernica. It also gave me his birthdate, something I did not know before. He was only 25 years old and he spent the last 2½ years of his life as a POW in one of Franco’s forced labor “Batallon de Trabajadores” (Workers’ Battalion). His letters also told me that he spent those last couple months of his short life at the hospital in Ward #11, Bed #13. Another letter, also addressed to America, but this one from the nun who was in charge of Ward #11, told us that he died at 9AM, after receiving last rites. But that was not the only discovery that came from that internet search. I also found out that he had been buried, along with the other 268 Republican POWs that had died at that hospital from 1938 until 1940, in a common grave at a nearby cemetery in Guernica. Yes, that is the same Guernica that was bombed by Hitler’s Condor Legion, the event Picasso made famous.

It is hard to explain how it feels to go from knowing nothing but my uncle’s name and that he had “died” during the civil war to knowing exactly the date and time he died, where he died and the cause of his death, 85 years later. Up until I got all this information, Galo was just another name, another abstract death, just one of tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of lost souls that still wander aimlessly in our collective memories, without recognition from anyone who knew them, like they never existed. I often thought about where his body had been buried, was he thrown in some ditch like so many others had been? Will we ever know? But beyond that, I had nothing else to connect with, no way to think about what his life was like, about his experience in that brutal war. Nothing that gave me any clues about what kind of person he was, what he had done in his short life, what his hopes and goals might have been for a life he never got a chance to live.

Then came the news that he had been captured and was a POW in one of those forced labor units. Now I had a glimpse into what his last couple of years on Earth might have been like. We know from numerous accounts, what Republican soldiers in those units went through, we know they were often worked to death. I remember hearing when I was young that many of Franco’s prisoners had “volunteered” to be in these units because they were promised reduced sentences, one year off for every year of work. Did Galo volunteer? Did he think that would be the way to be free and reunited with his family as soon as possible? And now what I had been told, that he had died of tuberculosis finally made sense. Conditions for soldiers in any war are always harsh but they tend to be a lot worse for POWs. Hunger, overcrowding, disease were a constant feature of daily life for these young men. It was yet another way to decimate the enemy.

And finally, we now know not only where and when he died but where he is buried and that solves another one of our family’s civil war mysteries. There is a place where his bones rest, where there is a marker with his name on it, where his life and his contribution are finally noted, his life is acknowledged, where his family can finally go to mourn for a life that didn’t have to end so soon. It is the kind of closure that still evades so many families, we are one of the few lucky ones that have learned where our dead rest, how their lives were extinguished by their own countrymen, just because they didn’t like their political and religious ideologies. Like his parents, Galo came to be buried in a common grave, with many other republican soldiers, all tossed together in one plot of land, away from the “proper” Catholic cemetery. I find some comfort in knowing where their bones are, it helps me try to process the immense grief this family was not allowed to honor. Now, only one is still missing; Jose Manuel, AKA Yoyo, Galo’s brother who killed himself rather than be captured. I am hopeful that he too will be found.

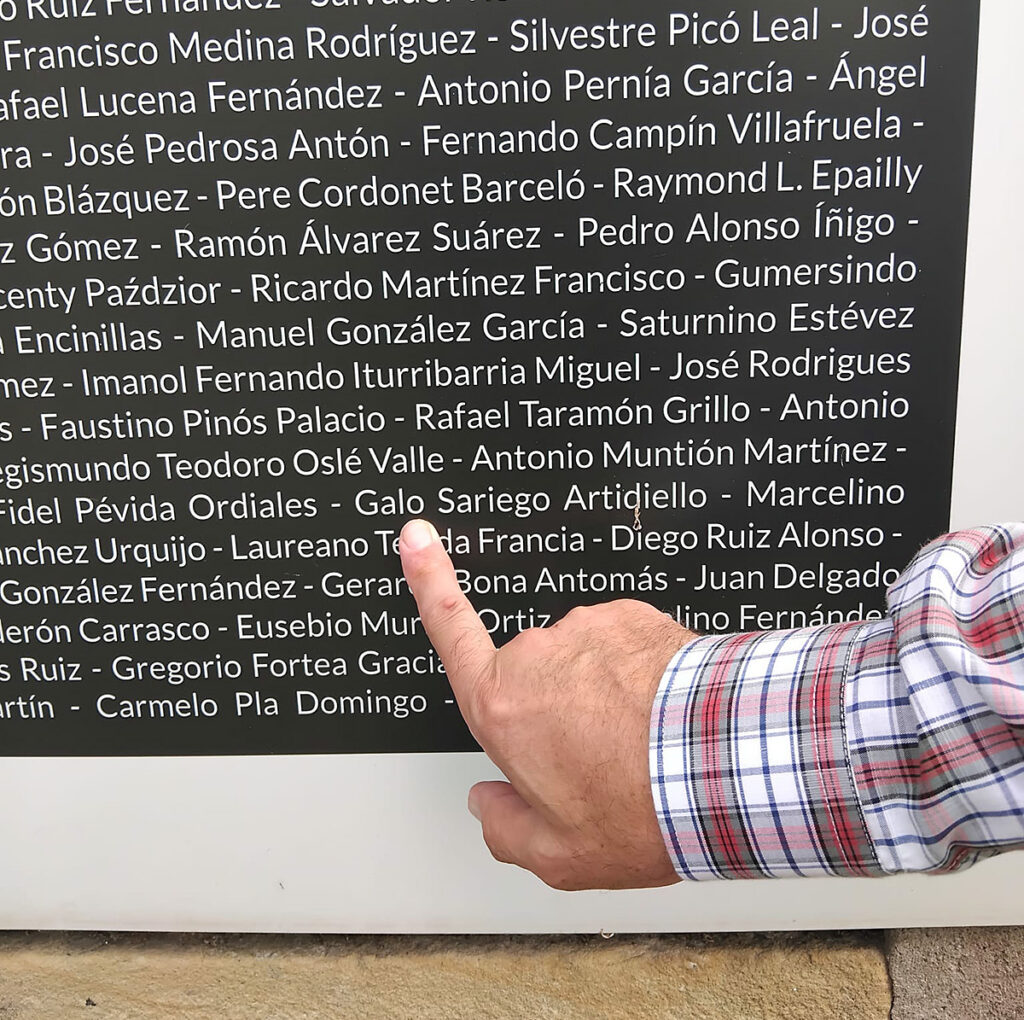

Just a few weeks ago, my cousin made the trip from Asturias to Guernica to find that common grave. What he found instead was that once the cemetery started running out of room, they exhumed the 269 bodies of the Republican soldiers, their bones now mixed together, and moved them to an osario común or communal bone grave. There is now a plaque at the cemetery, with all 269 names, honoring these men who had been forgotten for so long. There is also another one at the hospital, which is now a school. This recognition comes thanks to the tireless work of a handful of historical memory organizations, including Pipergorri Association. Our family is eternally grateful that thanks to them and their work, we now know where my uncle is buried, where he spent his last few months.

My cousin Paco points to Galo’s name on the plaque at the Guernica cemetery.

Galo left behind many letters, sent to his sister and brothers while he was held prisoner, doing his best to provide guidance to his younger siblings while fighting to survive under abysmal conditions in a forced labor military unit, in the hopes that someday, when the war was over, he could be reunited with them. It is hard to explain what a surreal and immensely sad experience it is to read these letters, written so long ago, by a young man who in his early 20s, while he himself was a POW, was left to try to be a father figure to his many younger brothers and sisters. In several of those letters, he asks his relatives, even a neighbor, for help, for money to buy medicine because he is sick, to buy necessities like shoes and food. He often talks about how anxious and worried he gets when he doesn’t get timely replies to his letters. He is constantly asking them to please let him know that they are OK.

But the most difficult letters for me where those sent after the war was finally over, from the Spring of 1939 until he passed away. In a few of those letters, he talks about his expectation that “soon,” he might have wonderful news, he might have a big “surprise.” He is expecting he will be released, as some of the POWs were being released and allowed to go back home. But the rest of that year came and went. His letter home a few days before Christmas was especially poignant as he tells his sister that he hopes they will all have wonderful holidays and that “yo las pasaré lo mejor que puedo.” (I will do my best to enjoy them.)

It is through these letters that I now feel like I have a little window into the life of a young man whose life was way too short, who died all alone, far from the people he loved, in a military hospital run by his enemies, by people who were hoping he would die. One less “rojo” soldier to contend with. Thank you, Galo, for writing those letters, for doing all you could to watch over your young brothers and sisters, for leaving that tiny bit of your life behind for us to get a sense of the caring, loving older brother who always made sure to tell them how much you loved them and never forgot about them. And thank you America, for keeping those letters so we can pass them along to the younger Sariegos so they get to know about Galo, a brother that was rarely mentioned during those Franco years, all but forgotten, like my grandparents. I wish I knew more of all their lives, I wish more of their stories had survived them, but I also try to remind myself that I know more now than I ever did and, that unlike so many other Spanish families, we are so fortunate to know where our dead are buried, and that they are finally being honored and remembered, not just by their relatives but by a nation that can now recognize their courage, their strength, when faced with the unimaginable nightmare that was the Spanish Civil War.

On my to do list is the translation of Galo’s letters, so they can be posted here. There is still much work to do, much more to document and write about this family, these ancestors that are for me the foundation of a family with much to be proud of and celebrate. I have no doubt they all had plenty of human flaws, I am sure there is plenty we might disagree on but I am also honored to be one of their descendants and every day I do my best to live my life in a way that might make them as proud of me as I am of them.

Zallo Cemetery – Gernika-Lumo, where 269 Republican POWs who died at the Gernika Military Hospital are buried, including my uncle Galo.

Leave a Reply to TheGranddaughter Cancel reply