“[Our] psyche … also extends out into the world, a world we are part of — a world we are impacted by and that we impact ourselves. Nothing about us can be understood without understanding our contexts — the ones we have lived in and depended on, and those we live in and depend on now.” Felicia Katarina Lundgren

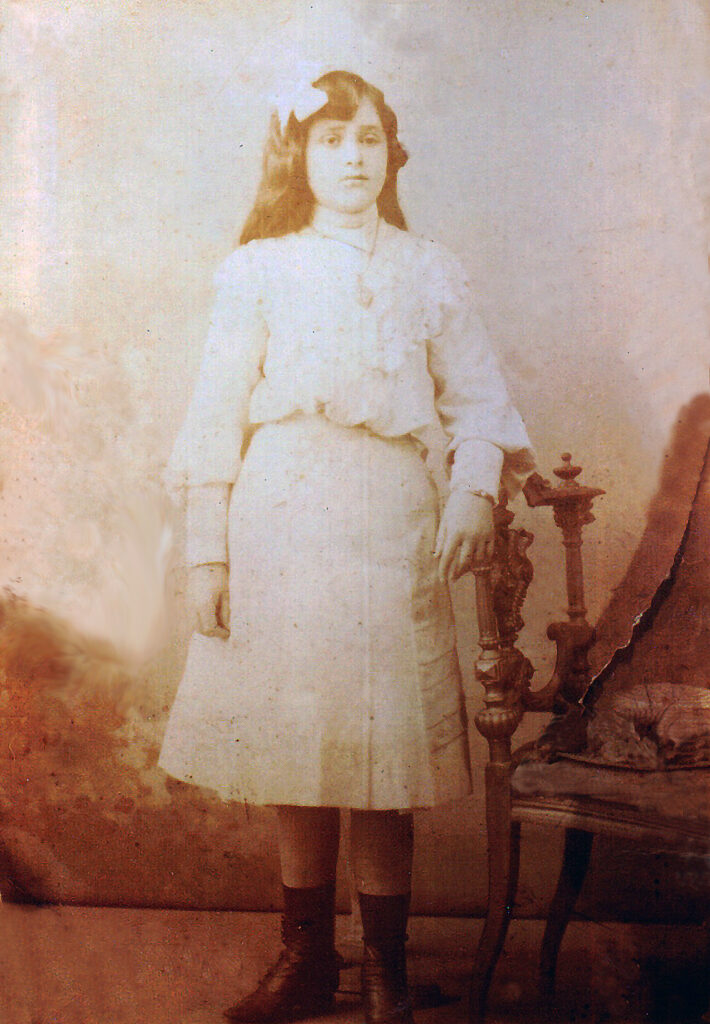

My grandmother was born in Havana, Cuba. If official records of her death are correct, in the year 1892, just 3 years before Cuba’s second war for independence and 6 from the better known Spanish-American War. Sadly, we have been unable to find any documentation of her birth. Are birth records from that time still available? If they are, it appears the only way to track them down at this point is to travel to Havana.

She was the first and only child born to a couple that had emigrated to Cuba from Northern Spain, as that country was in its final days of empire. The parallels to my own life – or perhaps symmetry would be a better word to describe it – are sometimes hard for me to comprehend. She was born into a society that was desperately clinging to possessions they came by through murderous and quite often genocidal means. Like my great-grandparents, I was also born in Northern Spain but I now live, at the end of my life, in another country, the same one that played a critical role in ending Spain’s control over Cuba. And as was the case for Spain in the late 19th century, the country I live in appears to be heading in the same direction Spain was then, after having come to its turn at world domination through similar – one might say essentially identical – tactics.

My family’s story has always been that my great-grandparents, especially my great-grandfather believed that an education was a very important and valuable thing to have. Most unusual for that time, he is said to have believed that an education was just as important for girls as it was for boys.

We do not know for sure but it is a good bet my grandmother was educated in Havana. The education system in Spain was lagging compared to what apparently was happening in Havana in the late 1800s, at least when compared to rural areas and the education of the working class. Never mind that schools in Spain were typically off limits or had very limited access for girls and women. In addition, the overwhelming majority of schools there were run and controlled by the Roman Catholic Church, so religious indoctrination, especially with girls, took precedence over all other subjects.

Not only was my grandmother said to be highly educated considering those times, everyone who spoke about her, including the teacher I had growing up, whose family had known her, said she was very intelligent.

One thing that occurred to me the other day is the irony that her having been born in Havana – in a place and to parents that were more progressive than most, where she was not only allowed but encouraged to learn, to get an education, where her intelligence was recognized and nurtured, where she was exposed to the subjects and ideas that were totally out of the question for women in Infiesto, Asturias during the 1930s – could have been the critical factor that led to her tragic end.

Think about it this way. If she had been born in that backward part of Spain, she would most likely have been like the majority of the women in that village: unable to read, never exposed to other ideologies but the one that said women weren’t smart enough to vote, to have an opinion about anything outside their domestic sphere, to have a life or acceptable role outside of marriage and motherhood. And then, she wouldn’t have spent her time reading newspapers to neighbors who couldn’t read or talking politics with anyone, or joining the S.R.I. (Socorro Rojo Internacional or International Red Aid) or doing any of those things she was accused of doing. Like the rest of the women in that village, she would have been too busy raising her 11 children, cooking, cleaning, washing clothes by hand – there were no washing machines back then – and minding her own business. She certainly would not have been standing on top of that piano giving speeches, as some said she did. And no one would have even considered making up those stories about her, stories that led to charges that got her sentenced to death.

What reason would they have had to do such a thing? To be jealous of her as some say was their motive for the accusations? If she had been like them, if she had been “one of them,” she would have been another dutiful wife and mother and probably also a devout Catholic. And she would not have been a target for the Nationalists’ “limpieza,”1 carried out by Franco and his troops as they defeated the Republicans and their supporters in each region and village of Spain. City by city, pueblo by pueblo, anyone who was remotely viewed as a threat to his authority, to his “crusade,” was killed or jailed. They were all lumped together under the umbrella of being “rojos” (reds, communists, or “izquierdos”). Members of the Second Republic or those who supported them, anyone who voted for the Republic, teachers, union leaders and organizers, liberals, intellectuals, Protestants, atheists or even those who failed to attend Catholic mass on a regular basis, communists, socialists, anarchists, anyone who might have any leftist political leanings, artists, activists, feminists … in essence, anyone who “did not think like them” (Francoists, Carlists, Falangists, the rich, the Catholic Church) were seen as threats and systematically eliminated.

“It is necessary to spread terror,” one of Franco’s senior generals declared. “We have to create the impression of mastery, eliminating without scruples or hesitation all those who do not think as we do.”2

There is not much documentation to support what little I know about my grandparents, about their life before their execution. In the absence of the “documented proof” we value above all else in our modern, rational world, the best I can do is to make educated guesses as to what was going on in that family. I can look at some of our accepted concepts about how things work with us humans, in family systems, within the context of the historical record of what was happening in their lives, in that place.

Their two oldest sons chose to fight against the nationalists. Did they do that of their own accord? Or because of the influence of their parents’ ideologies? Either way, they went left, rather than right. So it seems to have been the case for at least some of their remaining children, some of their grandchildren and even great-grandchildren.

I don’t know, maybe I am just stubbornly clinging to my own personal hope that my grandparents were indeed opposed to Franco and the Nationalists’ ideologies, regardless of how personally involved they were in opposition activities. I don’t know that I could make peace with the idea that this woman I have been so obsessed with, that I have idolized for so long, was the opposite of what she was accused of being, that she was a Franco supporter. Is that one of my blind spots? Could be, I guess. But, what evidence we do have, says she was not “one of them.”

And I suspect my cousin Ramon would have been equally devastated if our grandfather turned out to be a Falangist, as opposed to a member of the UGT (Union General de Trabajadores) as he was said to be. It is also interesting to think about how resistant some of our family were/are to the idea that grandma was political, that she might have been a “communist” but I don’t ever recall anyone denying that grandpa was a union member or saying he was “not political.” Although, the way my father told it, grandma was definitely more outspoken about politics than grandpa or at the very least, grandpa was much more “discrete” about discussing his views with others. I don’t ever recall anyone saying grandpa was out and about town reading newspapers to neighbors. Of course, that might have been due to him being 10 years older, his personality being different than grandma’s … and the fact that he was a man. There was much more to be enraged and outspoken about against the society they lived in if you were a woman. That was the case then as it continues to be now.

For a fascinating and in-depth discussion of the education system in Havana and Spain during the late 1800s and early 1900s, consider reading this article. If my grandmother was educated in Havana and depending on what schools she attended, it would not be surprising that her personal and political views evolved as they supposedly did.

1. The word “limpieza” means “a cleaning.” In this context, it indicated a “cleansing” of the unwanted elements in Spanish society. “Though there was much wanton killing in rebel Spain, the idea of the limpieza, the ‘cleaning up’ of the country from the evils which had overtaken it, was a disciplined policy of the new authorities and a part of their programme of regeneration. In Republican Spain, most of the killing was the consequence of anarchy, the outcome of a national breakdown, and not the work of the state.” Retrieved 3/22/18 from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_Terror_(Spain)

2. Hochschild, A. (2012, May 13). Process of Extermination. Retrieved March 22, 2018, from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/13/books/review/the-spanish-holocaust-by-paul-preston.html. Accessed 3/22/18.

Leave a Reply to Christina Cancel reply